In my last post , I talked about a new feature of Windows Server 2016, Discrete Device Assignment. This post will discuss the machines and devices necessary for making this feature work.

First, we're not supporting Discrete Device Assignment in Hyper-V in Windows 10. Only Server versions of Windows support this. This isn't some wanton play for more of your hard-earned cash but rather just a side effect of being comfortable supporting server-class machines. They tend to work and be quite stable.

Firmware, including BIOS and UEFI, Must Cooperate

Second, in order to pass a device through to a guest VM, we have to change the way parts of the PCI Express fabric in the machine are configured. To do this, we need the firmware (BIOS, UEFI, whatever) in the machine to agree that it won't change the very same parts of PCI Express that Windows is changing while the machine is running. (Yes, the BIOS does actually do things while the machine is running.) So, in accordance with the PCI firmware specification, Windows asks the firmware for control of several different parts of PCIe.

This protocol was created when PCIe was new, largely because Windows XP, Windows Server 2003 and many other operating systems were published before the PCI Express specification was done. BIOSes in these machines needed to manage PCIe. Windows, or any other operating system, essentially asks the BIOS whether it is prepared to give up this control. The BIOS responds with a yes or a no. If you BIOS responds with a no, then we don't support Discrete Device Assignment because we may destabilize the machine when we enable it.

Another requirement of the underlying machine is that it exposes "Access Control Services" in the PCI Express Root Complex. Pretty much every machine sold today has this hardware built into it. It allows a hypervisor (or other security-conscious software) to force traffic from a PCI Express device up through the PCIe links (slots, motherboard wires, etc.) all the way to the I/O MMU in the system. This shuts down the attacks on the system that a VM might make by attempting, for instance, to read from the VRAM by using a device to do the reading on its behalf. And while nearly all the silicon in use by machine makers supports this, not all the BIOSes expose this to the running OS/hypervisor.

Lastly, when major computer server vendors build machines, sometimes the PCI Express devices in those machines are tightly integrated with the firmware. This might be, for instance, because the device is a RAID controller, and it needs some RAM for caching. The firmware will, in this case, take some of the installed RAM in the machine and sequester it during the boot process, so that it's only available to the RAID controller. In another example, the device, perhaps a NIC, might update the firmware with a health report periodically while the machine runs, by writing to memory similarly sequestered by the BIOS. When this happens, the device cannot be used for Discrete Device Assignment, as exposing it to a guest VM would both present a considerable security risk and because the view of memory from within the guest VM is entirely different than the view of the actual system hardware, and thus the attempts by the devices to read and write this private memory would fail or corrupt other memory.

There are a lot of other low level requirements, many of them documented by John Howard in his SR-IOV series, but most of the machines in the world will conform with them, so I won't go into more detail now.

Beyond the BIOS, individual devices may or may not be candidates for passing through to a VM

Some devices in your computer don’t mark, or tag, their traffic in way that individually identifies the device, making it impossible for the I/O MMU to redirect this traffic to the memory owned by a specific VM. These devices, mostly older PCI-style logic, can’t be assigned to a guest VM.

All of the devices inside your computer have some means to control them. These controls are built out of “registers” which are like locations in computer memory, but where each location has a special purpose, and some sort of action that happens when the software reads or writes that location. For instance, any devices have “doorbell” registers which tell them that they should check work lists in memory and do the work described by what is queued up on the work lists. Registers can be in locations in the computer’s memory space, in which case they’re commonly called “memory-mapped I/O” and the processor’s page tables allow the hypervisor to map the device’s register into any VM. But registers can also be in a special memory-like space called “I/O space.” When registers are in I/O space, they can’t be redirected by the hypervisor, at least not in a friction-free way that allows the device and the VM to run at full speed. As an example, USB 1 controllers use I/O ports. USB 3 controllers use memory-mapped I/O space. So USB 3 controllers might meet the criteria for passing through to a guest VM in Hyper-V.

PCI-style devices have two possible ways to deliver interrupts to the CPUs in a computer. They can connect a pin to a ground signal, somewhat like unplugging a light bulb, or they can write to a special location in the processor directly. The first mechanism was invented many years ago, and works well for sharing scarce “IRQs” in old PCs. Many devices can be connected to the same metaphorical light bulb, each with its own stretch of extension cord. If any device in the chain wants the attention of the software running on the CPU, it unplugs its extension cord. The CPU immediately starts to run software from each device driver asking “was it you who unplugged the cord?” The problem comes in that, when many devices share the same signal, it’s difficult to let one VM manage one of the devices in that chain. And since this mechanism of delivering interrupts is both deprecated and not particularly common for the devices people use in servers, we decided to only support the second method of delivering interrupts, which can be called Message-Signaled Interrupts, MSI or MSI-X, all of which are equivalent for this discussion.

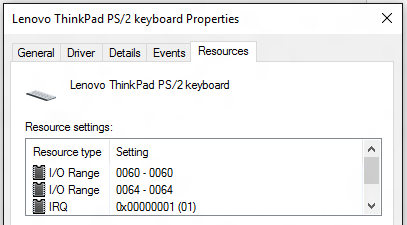

Some of the properties discussed are easily seen in the Device Manager. Here’s the keyboard controller in the machine that I’m typing this with. It fails all the tests described above.

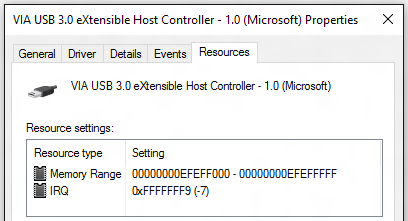

And here’s a USB 3 controller. The Message-Signaled Interrupts show up as IRQs with negative numbers. This device happens to pass all the tests.

Survey the Machine

To help you all sort this out, I've written a script which surveys the machine and the devices within it, reporting on which of them meet the criteria for passing them through to a VM.

You can download it by running the following command in PowerShell:

In my HP server machine, this returns a long list, including entries like:

Smart Array P420i Controller

BIOS requires that this device remain attached to BIOS-owned memory. Not assignable.

Intel(R) C600/X79 series chipset USB2 Enhanced Host Controller #2 - 1D2D

Old-style PCI device, switch port, etc. Not assignable.

NVIDIA GRID K520

Express Endpoint -- more secure.

And its interrupts are message-based, assignment can work.

PCIROOT(0)#PCI(0300)#PCI(0000)#PCI(0800)#PCI(0000)

The first two entries are for devices which can’t be passed through to a VM. The first is in side-band communication with the HP management firmware, and the HP BIOS stipulates that communication channel must not be broken, which would happen if you passed the device through to a VM. The second is for a USB 2 controller that’s embedded in the Intel chipset. It’s actually old-style PCI logic, and thus the I/O MMU can’t tell its traffic from any other device’s so it can’t handle being giving addresses relative to a guest VM.

The last entry, for the NVIDIA GRID K520, is one where the device and the machine meet the criteria for passing it through to a guest VM. The last line shows the “location path” for this GPU, which is in terms of “first root PCI bus; bridge at device 3, function 0; bridge at device 0, function 0; bridge at device 8, function 0; device 0 function 0.” This string isn’t going to change, even if you plug in another device somewhere else in the machine. The classic way of describing a PCI device, by bus number, device number and function number can change when you add or remove devices. Similarly, there are things that can affect the PnP instance path to the device that Windows stores in the registry. So I prefer using this location path, since it’s durable in the face of changes.

There’s another sort of entry that might come up, one where the report says that the device’s traffic may be redirected to another device. Here’s an example:

Intel(R) Gigabit ET Dual Port Server Adapter

Traffic from this device may be redirected to other devices in the system. Not assignable.

Intel(R) Gigabit ET Dual Port Server Adapter #2

Traffic from this device may be redirected to other devices in the system. Not assignable.

What this is saying is that memory reads or writes from the device targeted at the VM’s memory (DMA) might end up being routed to other devices within the computer. This might be because there’s a PCI Express switch in the system, and there are multiple devices connected to the switch, and the switch doesn’t have the necessary mechanism to prevent DMA from one device from being targeted at the other devices. The PCI Express specifications optionally allow all of a device’s traffic to be forced all the way up to the I/O MMU in the system. This is called “Access Control Services” and Hyper-V looks for that and enables it to be sure that your VM can’t affect others within the same machine.

These messages also might show up because the device is “multi-function” where that means that a single chip has more than one thing within it that looks like a PCI device. In the example above, I have an Intel two-port gigabit Ethernet adapter. You could theoretically assign one of the Ethernet ports to a VM, and then that VM could take control of the other port by writing commands to it. Again, the PCI Express specifications allow a device designer to put in controls to stop this, via Access Control Services (ACS).

The funny thing is that the NIC above has neither the ACS control structure in it nor the ability to target one port from the other port. Unfortunately, the only way that I know this is that I happened to have discussed it with the man at Intel who led the team that designed that NIC. There’s no way to tell in software that one NIC port can’t target the other NIC port. The official way to make that distinction is to look for ACS in the device. To deal with this, we allow you to override the ACS check when dismounting a PCI Express device. (Dismount-VMHostAssignableDevice -force)

Forcing a dismount will also be necessary for any device that is not supported. Below is the output of an attempt to dismount a USB 3 controller without forcing it. The text is telling you that we have no way of knowing whether the operation is secure. And without knowing all the various vendor-specific extensions in each USB 3 controller, we can’t know that.

PS C:\> Dismount-VMHostAssignableDevice -LocationPath "PCIROOT(40)#PCI(0100)#PCI(0000)"

Dismount-VMHostAssignableDevice : The operation failed.

The manufacturer of this device has not supplied any directives for securing this device while exposing it to a

virtual machine. The device should only be exposed to trusted virtual machines.

This device is not supported when passed through to a virtual machine.

The operation failed.

The manufacturer of this device has not supplied any directives for securing this device while exposing it to a

virtual machine.

Use the “-force” options only with extreme caution, and only when you have some deep knowledge of the device involved. You have been warned.

Read the next post in this series: Discrete Device Assignment -- GPUs

-- Jake Oshins

Microsoft

Microsoft