A while back we promised an article on namespace planning and load balancing principles with Exchange 2013. We’re finally going to fulfill that promise as a series of articles. The articles will span several topics, including namespace planning, load balancing, client connectivity coexistence, and certificate planning. As the title suggests, this first article will cover namespace planning principles.

Namespace Planning

If you are like the vast majority of our customers, you already have some version(s) of Exchange deployed in your environment. Depending on the version, you may have different namespace requirements today.

Exchange 2007

In Exchange 2007 environments, at a minimum, you had two namespace scenarios:

- An Autodiscover namespace – autodiscover.contoso.com.

- One or more protocol-based namespaces – mail.contoso.com (for OWA, EAS, etc.); imap.contoso.com (for POP/IMAP clients); smtp.contoso.com (for SMTP client submissions, ad-hoc encryption or partner-to-partner encryption).

In addition, if you deployed in a multi-datacenter environment, you most likely had additional protocol-based namespaces for each region.

Exchange 2010

Like Exchange 2007, Exchange 2010 leverages the Autodiscover service for enabling client profile changes, so that namespace exists.

For customers that upgraded from Exchange 2007 (or Exchange 2003), a new namespace requirement was introduced for coexistence – the legacy namespace, legacy.contoso.com. Though it is important to note that the legacy namespace can be called anything you choose, alderaan.contoso.com for example.

Exchange 2010 introduced additional namespace requirements, which resulted in additional complexity around namespace planning, especially for site resilient solutions:

- Primary datacenter Internet protocol namespace (mail.contoso.com)

- Secondary datacenter Internet protocol namespace (mail2.contoso.com)

- Primary datacenter Outlook Web App failback namespace (mailpri.contoso.com)

- Secondary datacenter Outlook Web App failback namespace (mailsec.contoso.com)

- Transport namespace (smtp.contoso.com)

- Primary datacenter RPC Client Access namespace (rpc.contoso.com)

- Secondary datacenter RPC Client Access namespace (rpc2.contoso.com)

Out of these nine namespaces, seven of them were required on certificates. The RPC Client Access namespaces were not required on the certificate because they were accessed via RPC connectivity and not via an Internet-based protocol, like HTTP.

Exchange 2013

One of the benefits of the Exchange 2013 architecture is that the namespace model can be simplified, when compared to Exchange 2010.

An example of how it can be simplified can be seen when thinking about a site resilience scenario. If you have two datacenters participating in a site resilient architecture, by replacing the Exchange 2010 infrastructure with Exchange 2013, five namespaces could potentially be removed:

- Secondary datacenter Internet protocol namespace (mail2.contoso.com)

- Primary datacenter Outlook Web App failback namespace (mailpri.contoso.com)

- Secondary datacenter Outlook Web App failback namespace (mailsec.contoso.com)

- Primary datacenter RPC Client Access namespace (rpc.contoso.com)

- Secondary datacenter RPC Client Access namespace (rpc2.contoso.com)

There’s two reasons for this.

First, Exchange 2013 no longer leverages an RPC Client Access namespace. This is due to the architectural changes within the product - for a given mailbox, the protocol that services the request is always going to be the protocol instance on the Mailbox server that hosts the active copy of the database for the user’s mailbox. In other words, the RPC Client Access service is no longer decoupled from the store, like it was in Exchange 2010.

Second, as mentioned, CAS2013 proxies requests to the Mailbox server hosting the active database copy. This proxy logic is not limited to the Active Directory site boundary. Unlike Exchange 2010, Exchange 2013 does not require the client namespaces to move with the DAG during an activation event – a CAS2013 in one Active Directory site can proxy a session to a Mailbox server that is located in another Active Directory site. This means that unique namespaces are no longer required for each datacenter (mail.contoso.com and mail2.contoso.com); instead, only a single namespace is needed for the datacenter pair – mail.contoso.com. This also means failback namespaces are also not required during DAG activation scenarios, so mailpri.contoso.com and mailsec.contoso.com are removed.

Namespace Models

Depending on your architecture and infrastructure you have two choices:

- Deploy a unified namespace for the site resilient datacenter pair (unbound model).

- Deploy a dedicated namespace for each datacenter in the site resilient pair (bound model).

It’s also worth mentioning that these choices are also tied to the DAG architecture.

Unbound Model

In an unbound model, you have a single DAG deployed across the datacenter pair. This DAG has Mailbox servers in each datacenter – typically all Mailbox servers are active and host active database copies, however you could deploy all active copies in a single datacenter. Mailboxes for both datacenters are dispersed across the mailbox databases within this DAG. In this model, clients can connect to both datacenters in the event there is a WAN failure – neither datacenter’s connectivity is a boundary, hence the term unbound. It does not guarantee, however, the connectivity provides users an equal experience; meaning one connection may provide a better user experience because it has lower latency or more bandwidth.

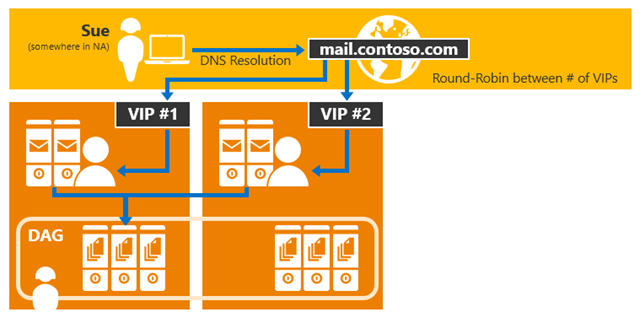

In an unbound model, a single namespace is preferred because either datacenter can service the user request. This means that from a load balancing perspective, the CAS infrastructure in both datacenters participate in handling traffic, as seen in the following diagram:

Figure 1: Single Namespace used across Site Resilient Datacenter Pair (Unbound Model)

As a result, for a given datacenter, the expectation is that 50% of the traffic will be proxied from the other datacenter.

Bound Model

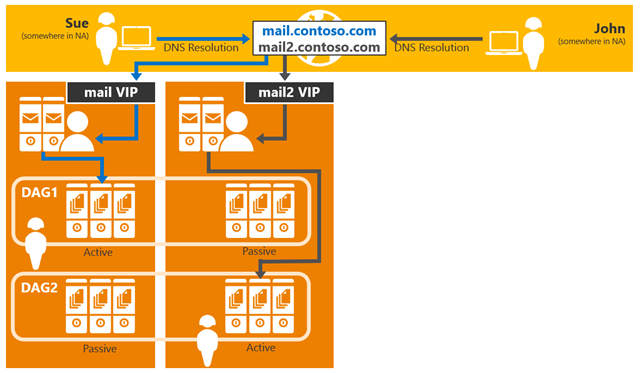

As its name implies, in a bound model, users are associated (or bound) to a specific datacenter. In other words, there is preference to have the users operate out of one datacenter during normal operations and only have the users operate out of the second datacenter during failure events. There is also a possibility that users do not have equal connectivity to both datacenters. Typically, in a bound model, there are two DAGs deployed in the datacenter pair. Each DAG contains a set of mailbox databases for a particular datacenter; by controlling where the databases are mounted, you control connectivity.

In a bound model, multiple namespaces are preferred, two per datacenter (primary and failback namespaces), to prevent clients trying to connect to the datacenter where they may have no connectivity. Switchover to the other datacenter is a controlled event.

Figure 2: Multiple Namespaces used across Site Resilient Datacenter Pair (bound Model)

Other Namespaces

Other namespaces are still required. Exchange 2013 takes advantage of the Autodiscover service for client profile manipulation; so the autodiscover.contoso.com namespace remains in place.

If you are planning to upgrade from Exchange 2007, a legacy namespace is required for connectivity. The legacy namespace provides connectivity for OWA, is the namespace returned in Autodiscover responses (e.g., Exchange Web Services URL), and provides access to Exchange 2007 mailboxes that exist in non-Internet facing Active Directory sites.

Internal vs. External Namespaces

Since the release of Exchange 2007, the recommendation is to deploy a split-brain DNS infrastructure for the Internet-based client namespaces. A split-brain DNS infrastructure enables different IP addresses to be returned for a given namespace based on where the client resides – if the client is within the internal network, the IP address of the internal load balancer is returned; if the client is external, the IP address of the external gateway/firewall is returned.

This approach simplifies the end-user experience – users only have to know a single namespace (e.g., mail.contoso.com) to access their data, regardless of where they are connecting. A split-brain DNS infrastructure, also simplifies the configuration of Client Access server virtual directories, as the InternalURL and ExternalURL values within the environment can be the same value.

In the event that you do not deploy a split-brain DNS (also known as split-DNS) infrastructure, Exchange 2013 has introduced one improvement in this area – Outlook Anywhere now supports separate internal and external namespaces.

Regional Namespaces

The concept of regional namespaces has existed since OWA debuted in 1997 (can you believe OWA is almost 17 years old!?!). A regional namespace is a way for clients to connect to the Client Access endpoint that is closest to the Mailbox servers hosting the data.

Use of a regional namespace does not necessarily mean you are restricted to a bound model, either. This is because depending on your infrastructure and network capabilities, you may choose to have a dedicated namespace for each datacenter pair. For example, your company may have a set of datacenters in North America and in Europe, and due to a desire to reduce cross-region network traffic, you deploy a dedicated namespace for each region (notice that within a region, the unbound model is used):

Conclusion

Exchange 2013 introduces significant flexibility in your namespace architecture, enabling deployment of a single unified namespace for a site resilient datacenter pair (or worldwide), or deployment of multiple namespaces. As we delve into the intricacies surrounding load balancing principles, client connectivity, and certificate planning, you will understand (hopefully) how to choose the best namespace model.

Ross Smith IV

Principal Program Manager

Office 365 Customer Experience

Updates

- 3/10/2014: Added note regarding the impact to Outlook Anywhere with respect to namespaces and authentication settings used.