- Home

- Skype for Business

- Skype for Business Blog

- Piping and the Pipeline

- Subscribe to RSS Feed

- Mark as New

- Mark as Read

- Bookmark

- Subscribe

- Printer Friendly Page

- Report Inappropriate Content

Quick: What one feature truly separates Windows PowerShell from other scripting/shell languages? How many of you said “the pipeline?” Really? That many of you, huh?

I t’s inevitable: no sooner do you get Windows PowerShell installed then you start hearing about “piping” and “the pipeline.” In turn, that leads to two questions: 1) What’s a pipeline?; and, 2) Do I even need to know about piping and pipelines?

Let’s answer the second question first: Do you even need to know about piping and pipelines? Yes, you do. There’s no doubt that you can work with Windows PowerShell without using pipelines. The question, however, is whether you’d want to work with PowerShell without using pipelines. After all, you can order a banana split and ask them to hold the ice cream; that’s fine, but at that point you don’t really have a banana split, do you? The same is true of the PowerShell pipeline: you can run commands and write scripts without a pipeline. But, at that point, are you really making use of PowerShell ?

Note . OK, we’re exaggerating a little bit: many commands don’t need a pipeline. In general, however, that’s not going to be true of longer and more complicated PowerShell commands and scripts.

But we weren’t exaggerating about banana splits. They really do all need to have ice cream.

Assembling a Pipeline

So then what is piping and the pipeline? To begin with, the term “pipeline” can be considered something of a misnomer. Suppose you have an oil pipeline, like the Alaska Pipeline. You put oil in one end of the pipeline; what do you suppose comes out the other end? You got it: oil. And that’s the way a pipeline is supposed to work: it’s just a way of moving something, unchanged, from one place to another. But that’s not the way the pipeline works in Windows PowerShell.

Note: To be honest, we’ve had some internal debate about this whole pipeline metaphor: There have been some interesting discussions around the PowerShell water cooler about this topic that involve Kool-Aid and waste management facilities (don’t ask), as well as mentions of marketing pipelines and other industry-specific terminology, but we won’t confuse you with all that. You’re probably confused enough already, and, seeing as how our goal is to un -confuse you, we’ll move on.

Instead, think of the Windows PowerShell pipeline as being more like an assembly line. With an assembly line you start with a particular thing; for example, you end up with a car. However, you don’t start with a finished car; instead, at each station workers make some sort of modification, welding on doors, adding windows, installing seats. When you’re all done you’ll have a car; you won’t have a tube of toothpaste or a barrel of oil. But thanks to all the changes that were made along the way, you’ll have a very different car than the “car” you started with. That’s really the way PowerShell’s pipeline works. You grab an object, and, each time you pass it through the pipeline, another cmdlet modifies that object in some way (by adding properties, by deleting properties, by sorting or grouping, etc.).

To better illustrate what we’re talking about here, let’s walk through the pipeline, step-by-step.

And yes, you probably should put on your boots.

Step 1: Returning an Object (or Objects)

Suppose there happened to be a cmdlet named Get-Shapes; when you run this cmdlet it returns a collection of all the geometric shapes found on your computer. To call this hypothetical cmdlet you’d use a command similar to this:

Get-Shapes

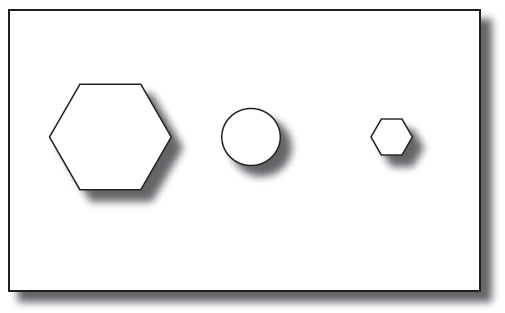

In return, you get back a collection like this one:

Step 2: The Filtering Station

That’s pretty cool – except for one thing. As it turns out, we’re only interested in the clear shapes; however, our hypothetical Get-Shapes cmdlet doesn’t allow us to filter out items that fail to meet specified criteria. Guess we’re out of luck, right?

Right.

No, wait, we mean wrong . Granted, Get-Shapes doesn’t know how to filter out unwanted items. But that’s not a problem, because PowerShell’s Where-Object cmdlet does know how to filter out unwanted items. Because of that, all we have to do is use Get-Shapes to retrieve all the shapes, then hand that collection of shapes over to Where-Object and let it filter out everything but the clear shapes. In other words:

Get-Shapes | Where-Object {$_.Pattern –eq "Clear"}

Don’t worry about the syntax of the Where-Object cmdlet for now. The important thing to note is the pipe separator (the | character) that separates our two commands (Get-Shapes and Where-Object). When we use the pipeline in Windows PowerShell that typically means that we use a cmdlet to retrieve a collection of objects. However, we don’t do anything with those objects, at least not right away. Instead, we hand that collection over to a second cmdlet, one that does some further processing (filtering, grouping, sorting, etc.). That’s what the pipeline is for.

And in our hypothetical example, the pipeline provides a way for us to filter out everything except the clear shapes:

Step 3: The Sorting Station

That’s cool, but what’s even cooler is the fact that you aren’t limited to just two stations on your assembly line. For example, suppose we want to now sort the clear shapes by size. Where-Object doesn’t know how to sort things. But Sort-Object does:

Get-Shapes | Where-Object {$_.Pattern –eq “Clear”} | Sort-Object Size

Does this really work? Of course it does:

A Real-Life Pipeline

Here’s a somewhat more practical use of the PowerShell pipeline. The command we’re about to show you uses the Get- ChildItem cmdlet to retrieve a list of all the items found in the folder C:\Scripts. The command then hands that collection over to the Where-Object cmdlet; in turn, Where-Object grabs all the items (files and folders) that are greater than 200Kb in size, filtering out everything else. After Where-Object finishes filtering, the cmdlet hands the remaining items over to the Sort-Object cmdlet, which sorts those items by file size.

The command itself looks like this:

Get-ChildItem C:\Scripts | Where-Object {$_.Length -gt 200KB} | Sort-Object Length

And when we run the command we get back something along these lines:

Directory: Microsoft.PowerShell.Core\FileSystem::C:\Scripts

Mode LastWriteTime Length Name

---- ------------- ------ ----

-a--- 2/19/2007 7:42 PM 266240 scores.mdb

-a--- 5/19/2007 9:23 AM 328620 wordlist.txt

-a--- 12/1/2002 3:35 AM 333432 6of12.txt

-a--- 5/18/2007 8:12 AM 708608 test.mdb

That’s pretty slick, but those of you who’ve done much scripting seem a little skeptical. “OK, that is nice, but it’s not that big of a deal,” you say. “After all, if I write a WMI query I can do filtering right in my query. And if I write an ADSI script I can add a filter that limits my collection to, say, user accounts. I’m already doing all this stuff.”

Depending on how you want to look at it, that’s true; you can use filtering in either a WMI or an ADSI script. However, the approach used when writing a filter in WMI is typically very different from the approach used when writing a filter in ADSI. In turn, an ADSI filter is different from the approach used when writing a filter using the FileSystemObject. The advantage to Windows PowerShell, and to using the pipeline, is that it doesn’t matter what kind of data or what kind of object you’re working with; you just hand everything off to Where-Object and let Where-Object take care of everything.

Take sorting, to name another commonly-used operation. If you’re doing a database query (including ADO queries against Active Directory) you don’t need a pipeline; you can specify sort options as part of the query. But what if you’re doing a WQL query against a WMI class? That’s a problem: WQL doesn’t allow you to specify sort options. If you’re a VBScripter that means you have to do something crazy, like write your own sort function (or rely on a workaround like disconnected recordsets) just so you can do something as seemingly-simple as sorting data. Is that the case in PowerShell? You already know the answer to that, don’t you? Of course that’s not the case; in PowerShell you just pipe your data to the Sort-Object cmdlet, sit back, and relax. For example, say you want to retrieve information about the services running on a computer, then sort the returned collection by service status (running, stopped, etc.). Okey-doke:

Get-Service | Sort-Object Status | Format-Table

Note . You might have noticed that, as a bonus, we took the sorted data and piped it to the Format-Table cmdlet; that means the final onscreen display ends up as a table rather than a list.

Don’t Get Carried Away

Yes, this is easy isn’t it? In fact, about the only time you’ll ever run into a problem is if you get carried away and try pipelining everything in sight. Remember, you can’t pipeline something unless it makes sense to use a pipeline. It makes sense to pipeline service information to Sort-Object; after all, Sort-Object can pretty much sort anything. It also makes sense to pipe the sorted information to Format-Table; after all, Format-Table can take pretty much any information and display it as a table.

But consider this command:

Sort-Object | Get-Process

What’s this command going to do? Absolutely nothing. Nor should we expect it to do anything. After all, Sort-Object is designed to sort information and there’s nothing here to sort. (Incidentally, that’s a hint that Sort-Object should typically appear on the right-hand side of a pipeline. You need to first grab some information and then sort that information.)

Note . Are there exceptions to this rule? Sure. For example, suppose you have a variable $a that contains a collection of data. You can sort that data, and sidestep the pipeline altogether, by using a command like this:

Sort-Object –inputobject $a

Someday you might actually have to use an approach similar to this; as a beginner, however, you shouldn’t worry about it. Instead, you should get into the habit of using piping and the pipeline. Learn the rules first; later on, there will be plenty of time to learn the exceptions.

But even if there was something for Sort-Object to sort this command still wouldn’t make much sense. After all, the Get-Process cmdlet is designed to retrieve information about the processes running on a computer; what exactly would Get-Process do with any sorted information handed over the pipeline? For the most part, you first acquire something (a collection, an object, whatever) and then hand that data over the pipeline. The cmdlet on the right-hand side of the pipeline will then proceed to do some additional processing and formatting of the items handed to it.

As we implied earlier, when you do hand data over the pipeline make sure there’s a cmdlet waiting for it on the other side. The more you use PowerShell the more you’re going to be tempted to do something like this:

Get-Process | $a

Admittedly, that looks OK – it looks like you want to assign the output of Get-Process to the variable $a then display $a. However, it’s not going to work; instead you’re going to get an error message similar to this:.

At line:1 char:17

+ Get-Process | $a <<<<

+ CategoryInfo : ParserError: (:) [], ParentContainsErrorRecordException

+ FullyQualifiedErrorId : ExpressionsMustBeFirstInPipeline

We’ll concede that this can be a difficult distinction to make, but pipelines are used to string multiple commands into a single command, with data being passed from one command to the next. Furthermore, as that data gets passed from one section to another it gets transformed in some way: filtered, sorted, grouped, formatted, whatever. In the invalid command we just showed you, we’re not passing any data. Instead, we’ve really got two totally separate commands here: we want to use Get-Process to return information about the processes running on a computer and then, without transforming that data in any way, we want to store the information in variable $a and display that information. Because we really have two independent commands, we need two lines of code:

$a = Get-Process

$a

And if you’re bound and determined to do this all on a single line of code, separate the commands using a semicolon rather than the pipe separator:

$a = Get-Process; $a

But this isn’t pipelining, this is just putting multiple commands on one line.

Bonus Tip

OK, but suppose you wanted to get process information, sort that information by process ID, and then – instead of displaying that information – store the data in a variable named $a. Can you do that? Yes you can, just like this:

$a = (Get-Process | Sort-Object ID)

What we’re doing here is assigning a value to $a. Which value are we assigning it? Well, we’re assigning it the value we get back when we call the Get-Process cmdlet and then pipe the returned information to Sort-Object. This command works because we put parentheses around our Get-Process/Sort-Object command. Any time PowerShell parses a command, it carries out the instructions enclosed in parentheses before it does anything else. In this case, that means PowerShell first gets and sorts process information, then assigns that data to $a. Display the value of $a and see for yourself.

But if you’re a beginner, don’t worry too much about this bonus example. Get used to using pipelines in the “traditional” way, then come back here and start playing around with parentheses.

More on Pipelining

With any luck, this should be enough to get you started with piping and pipelines. Once you get comfortable with the basic concept you might want a little more technical information about pipelines. If so, just type the following from your Windows PowerShell command prompt:

Get-Help about_pipelines

Don’t assume that you can ignore pipelines and become a true Windows PowerShell user; you can’t. You can – and should – ask them to hold the maraschino cherry when ordering a banana split. But if you ask them to hold the ice cream, you’ll spend all your time wondering why people make Piping and the such a big deal about banana splits. Don’t make that same mistake with Windows PowerShell.

You must be a registered user to add a comment. If you've already registered, sign in. Otherwise, register and sign in.